What I like about Golden Mummies of Egypt—both the exhibition and the accompanying publication—is that it’s more than just about mummies. It’s about people and their hope for the afterlife at the time when Egypt was ruled by the Macedonian Greeks and subsequently the Romans. You’ll learn more regarding multiculturalism, self-representation, religious beliefs, and mummification. As you visit the exhibition or read the catalogue, you’ll realize that it’s also about lifting the veil on colonialism and racism in Egyptology.

A Colonial Enterprise

Egyptology is undeniably entangled with European economic and military interests in Egypt—because Egypt has been a gateway to Asia and an African country located at the crossroads of strategic trade routes to sub-Saharan Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. In 1882 Great Britain invaded Egypt, securing access to the Suez Canal, and it occupied the country for the next 40 years. Set against this historical backdrop, the heyday of archaeological exploration in Egypt—by adventurous, upper and middle-class white males—appears much less glamorous to our modern eyes. While archaeologists sought to learn more about ancient peoples and cultures, archaeology (which can otherwise foster understanding and acceptance of those different from us) was a colonial enterprise that promoted Eurocentric supremacy.

Archaeological digs were dominated by (more or less competent) Western excavators, who rarely credited the hundreds of Egyptian workers who did the strenuous excavation work. The gilded mummies and other objects featured in the exhibition were discovered at Hawara by Flinders Petrie’s skilled workmen. (The excavations took place in 1888–89 and 1910–11.) One of the repercussions of colonisation is the partage system (a French noun meaning sharing; in English also called division of finds) devised by Petrie and the French head of the Antiquities Service in Egypt. This meant that both the Egyptian Antiquities Service and the foreign excavators could share the discoveries—with Egypt having first right of refusal and ostensibly keeping the most important finds. (While this was a great step in helping Egypt keep its cultural heritage at home, the initiative mirrored the political and economic control of Egypt’s debts to Western powers.)

Through the partage of excavated material, many museums in Europe and the U.S. were able to build Egyptian collections—including the Manchester Museum. While there are just a few brief mentions about this in the exhibition, the Golden Mummies catalogue, available from the Manchester Museum, devotes a chapter to Britain’s colonial expansion into Egypt, putting archaeology, collection building, and the antiquities trade into their sociopolitical and economic contexts and highlighting how the finds from Hawara made their way to Manchester. This chapter is a fascinating and an eye-opening read, indeed.

The partage system officially ceased in the 1980s, when Egypt passed its 1983 antiquities law, and all excavated materials now remain in the country (as is the case with most countries around the world). Nowadays foreign museums are also becoming more transparent about the formation of their collections, especially if they are the result of colonization. Readers who wish to learn more about the colonial legacy of archaeology in Egypt can read Egyptian Archaeology and the Museum, available online (another fascinating read).

Petrie, Skulls, and Faces

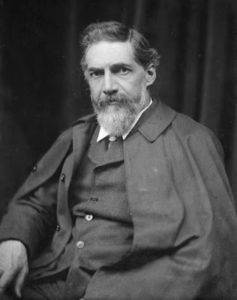

British archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie (1853–1942) is a looming figure in Egyptology. Commonly regarded as the “Father of Egyptian Archaeology,” Petrie was renowned for his scientific excavation methods (unlike his contemporaries) as well as his interest in the more mundane objects of daily life (again, unlike most of his peers). What was often unknown or relegated to a footnote by his biographers, however, is that Petrie was a proponent of eugenics—the “practice or advocacy of improving the human species by selectively mating people with specific desirable hereditary traits.”

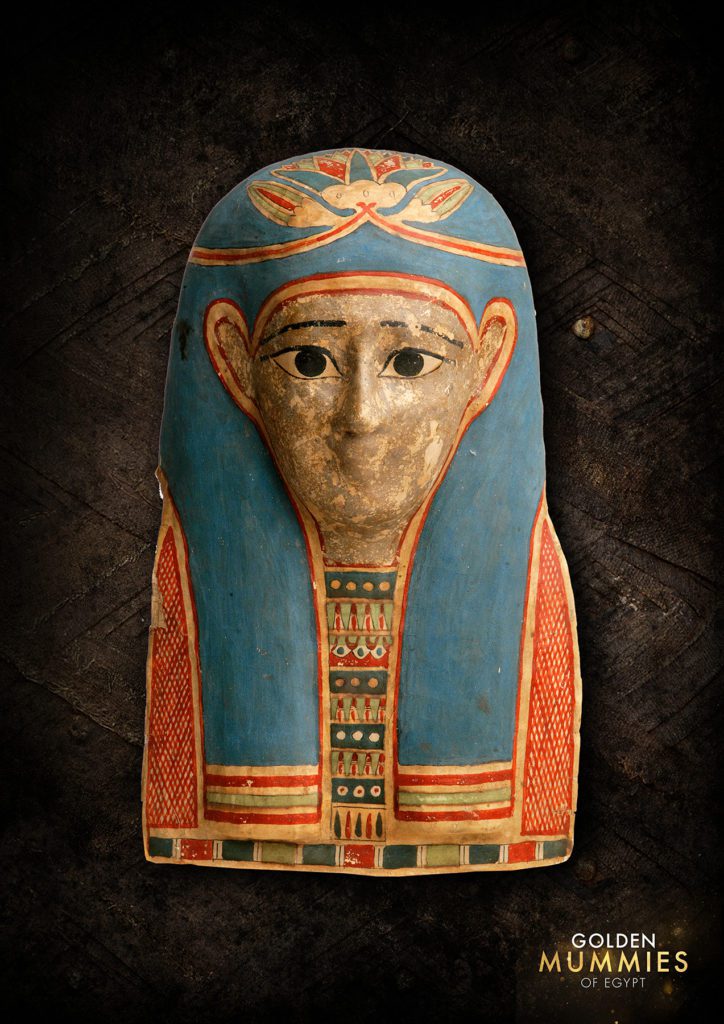

In his examination of the exposed skulls of mummies and their portraits from Hawara—including the spectacularly beautiful and naturalistic encaustic paintings, the so-called Faiyum portraits—Petrie used prejudiced opinions to argue for racial hierarchies. As one might imagine, Petrie “identified” Egyptian traits as not so favorable in comparison to European features. If one considers how codified and idealized Egyptian art is—even with more realistic Roman portraits—Petrie’s arguments are even more dubious because they are based on misinterpretation of the archaeological material. When one understands that the purpose of these portraits and masks was to liken the deceased to a god to facilitate rebirth in the afterlife, an exact likeness of the individual is not necessary, and thus these portraits cannot be used to create “facial reconstructions” of Egyptians in Greco-Roman Egypt.

One of the short video clips in the exhibition presents this topic. A blog post written by Manchester curator Campbell Price dives a little deeper into Petrie’s fascination with skulls and faces, and his April 17 lecture on the topic is available online.

Pharaonic Preferred

Petrie began work at Hawara with the intention of excavating the so-called “Labyrinth,” the funerary complex associated with the pyramid of Twelfth Dynasty King Amenemhat III. This wonderous labyrinth was renowned in antiquity—thought to be even more noteworthy than the Great Pyramid of Giza—and featured on the bucket list of Greek and Roman travelers to Egypt. However, the discovery of the Greco-Roman cemetery at Hawara diverted Petrie’s attention and funds from his exploration of the pyramid complex. (Very often archaeologists stumble on something new when looking for something else!) In his writings Petrie voices disdain for the Greco-Roman material coming out of the ground. What he was excavating did not compare to pharaonic monuments and material culture, clearly lacking that je ne sais quoi that makes pharaonic Egypt so appealing. Petrie’s comments are in complete contrast to his biased opinions of modern Egyptians.

While Petrie’s pharaonic biases are only hinted at in the exhibition, these are further discussed in the exhibition catalogue. Nonetheless, the entire exhibition is about this deliberately overlooked portion of Egyptian history, one that will appear very different from what visitors expect of ancient Egypt, but one that is utterly fascinating. That beloved little corner of northeast Africa continued to thrive, keeping many of its millennia-old traditions, despite having been colonized by the Macedonian Greeks and the Romans. My May 13 lecture, titled “Golden Mummies: Adapting Funerary Beliefs and Traditions,” which further elaborates on this topic, is now available online.

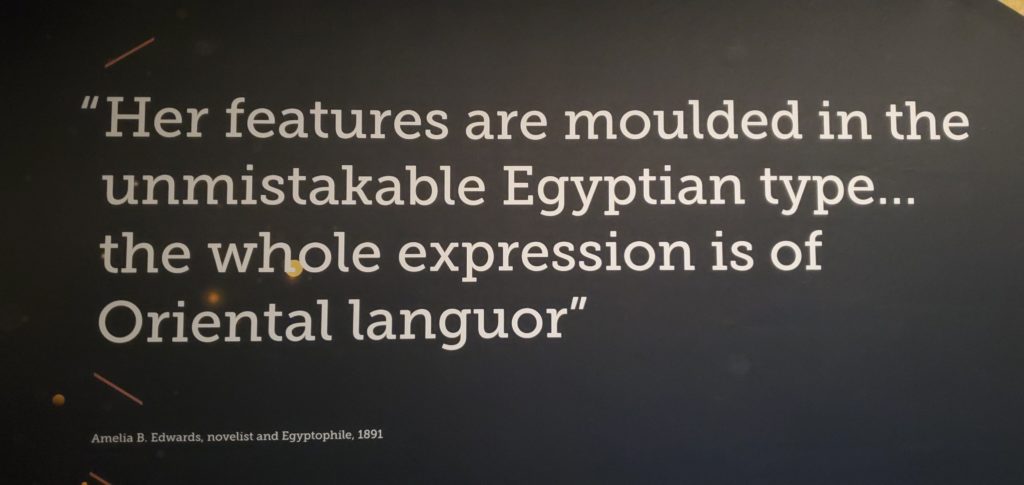

Quotes on the Walls

Visitors to the exhibition will notice in the seven sections large quotes on the walls. Some are quite lovely; others will make one pause because they do not seem culturally sensitive or appropriate—at least to our modern sensibilities. These words, spoken or written by Petrie and his contemporaries, reflect the biases of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The quotes invite visitors to reflect on racial and other prejudices and help us view the content of the exhibition with renewed awareness and sensibility.

The world has changed drastically since the Petrie excavations at Hawara that yielded the golden mummies found in the exhibition. Today new generations of Egyptologists are reassessing the archaeological material, revising the biases of past interpretation, and working toward redressing prejudiced views of Egypt and Africa that originated with the colonial history of Egyptian archaeology. Golden Mummies of Egypt is helping the field of Egyptology take a critical look at its past. Kudos to the Manchester Museum and Nomad Exhibitions for creating a mummy exhibition that is more than just about mummies.

Dismembering the Past: A Provocative New Acquisition That Re-Members History

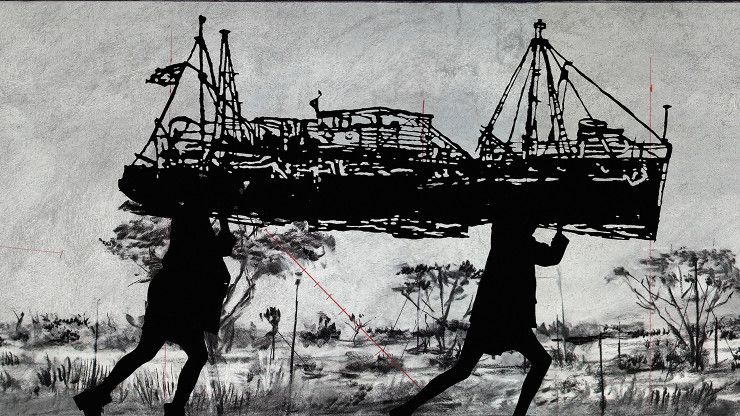

Curator Amanda Maples discusses the NCMA’s recent acquisition by renowned South African artist William Kentridge.

Introduction to Golden Mummies of Egypt

The NCMA’s first exhibition featuring mummies takes visitors on a fascinating tour of a little-known era in ancient Egypt, a time when multiculturalism reigned. Curator Caroline Rocheleau explains.

Bringing Mummies to Life

With the use of CT scans and digital technology, visitors to the Golden Mummies exhibition can explore what lies beneath the surface of ancient wrappings to discover more about ancient lives.