Conservation

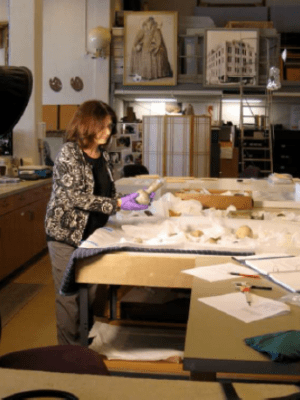

In support of the Museum’s mission to preserve the state’s collection, the Conservation Center is professionally staffed and organized to provide care, maintenance, and repair and restoration services for the priceless fine art collection of the Museum. In addition conservators provide support to all the Museum’s departments for programs and activities that affect the collection. Conservators are responsible for the preventive care necessary to slow or arrest the deterioration of the collection.

In the event of damage from accident or aging, the Museum’s conservators are uniquely qualified within the NCMA and the state to stabilize an art object and restore its aesthetic integrity. All work done on the collection is governed by a code of ethics and standards of practice outlined by the American Institute for the Conservation of Artistic and Historic Works.

Click here to learn more and go behind the scenes of the Bacchus Conservation Project.

Conservation

In support of the Museum’s mission to preserve the state’s collection, the Conservation Center is professionally staffed and organized to provide care, maintenance, and repair and restoration services for the priceless fine art collection of the Museum. In addition conservators provide support to all the Museum’s departments for programs and activities that affect the collection. Conservators are responsible for the preventive care necessary to slow or arrest the deterioration of the collection.

In the event of damage from accident or aging, the Museum’s conservators are uniquely qualified within the NCMA and the state to stabilize an art object and restore its aesthetic integrity. All work done on the collection is governed by a code of ethics and standards of practice outlined by the American Institute for the Conservation of Artistic and Historic Works.

Click here to learn more and go behind the scenes of the Bacchus Conservation Project.

Much of the 3,400-square-foot Conservation Center is devoted to studio space for treating and examining paintings, frames, and other works of art. The remaining space contains offices, a research library/analytical area, a studio for photography and radiography, and a room for the temporary storage of works of art during treatment.

The Conservation Center has a strong history of using resources that promote the training of conservation professionals. An ongoing program of Kress Conservation Fellowships is devoted to the research and treatment of European masterworks. For many years the Center additionally has offered conservation graduate school internships, summer internships, and training for volunteers in preparation for attending a conservation training program.

Recent and Ongoing Projects

- Eleonora di Toledo (1522–1562) and new frame

Studio of Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo), Italian, 1503–1572, 64.35.5 - Lucrezia de’ Medici (1545–1561)

Attributed to Alessandro Allori, Italian, 1535–1607, and assistants, 64.35.4 - The Raising of Lazarus

Domenico Tintoretto, Italian, circa 1560–1635, 60.17.49 - The Banquet of Cleopatra and Antony

Studio of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Italian, 1696–1770, 56.15.1 - Portable Altarpiece: Pietà, Saints Francis, Sebastian, John the Evangelist, Jerome, and John the Baptist

Circle of Bartolomé Bermejo, Spanish, circa 1435/40–circa 1500, 52.9.169 - Still Life with Strawberries and Chocolate

Juan Bautista Romero, Spanish, 1756–after 1802, 52.9.184 - Still Life with Pastries, Wine, and Eggs

Juan Bautista Romero, Spanish, 1756–after 1802, 52.9.185 - Portrait of Heinrich Crüdener

Bartel Bruyn the Younger, German, 1530–1610, 52.9.134 - Portrait of the Wife Heinrich Crüdener

Bartel Bruyn the Younger, German, 1530–1610, 52.9.135 - Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saints John the Evangelist, Peter, and Paul

Circle of Juan de Borgoña, Spanish, circa 1470–1536, 52.9.191 - Christ before Pilate

Lluis Borrassà, Spanish, circa 1360–circa 1425, 52.9.170

- Madonna and Child

Bartolommeo Bellano, Italian, 1430/35–1492/1500, 56.8.1 - The Creation

Unknown Flemish, active late 16th century, 52.9.98 - The Flight into Egypt

John Singer Sargent, American, 1856–1925, 2009.7.1 - The Madonna at Prayer

Sassoferrato, Giovanni Battisti Salvi, 1609–1685, TR.2007.48/2 LOAN 7.2007.2 - Sir William Pepperrell (1746–1816) and His Family

John Singleton Copley, American, 1738–1815, active in Great Britain 1774–1815, 52.9.8 - Ships in a Stormy Sea off a Coast

Ludolf Backhuysen, Dutch, 1631–1708, 98.13 - Christ and the Woman of Samaria

Pierre Mignard, French, 1612–1695, active in Rome 1635–1657/58, 52.9.127 - Kitchen Ball at White Sulphur Springs, Virginia

Christian Friedrich Mayr, American, born Germany (Bavaria), 1803–1851, 52.9.23 - St. Cosmas and St. Damian

Master of the Rinuccini Chapel, Italian, active 1350–1375, 60.17.9 - Oldfield Bowles

Attributed to Nathaniel Dance, British, 1735–1811, 52.9.87 - Untitled

Jean Hélion, French, 1904–1987, 57.40.1

Frequently Asked Questions

Conservators

Search for conservators across the country at the American Institute for Conservation and Preservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC).

Appraisals

While the North Carolina Museum of Art cannot provide appraisals for works of art, there are several organizations that can help locate local qualified professionals who can assist you with the valuation of your artwork.

American Society of Appraisers

(800) 272-8258

The Appraisers Association of America

(212) 889-5404

Art Dealers Association of America

(212) 488-5530

Please note: The Museum does not recommend or endorse particular appraisers or art dealers.

Other Resources

Care of any collection is based on proper long-term maintenance that includes safe handling, storage, and display. NCMA conservators are specifically trained in the care of painting collections and works of art on paper.

Download a conservation primer.

Conservators are responsible for the long-term preservation of artistic and cultural artifacts. They often specialize in a particular material or group of objects and work in a variety of environments. Specific details, including a guide to education and training, are available from the American Institute for Conservation and Preservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC).

Very carefully! The first ingredient of a successful cleaning treatment is experience. There is simply no substitute for the experience that a trained conservator brings to a treatment. This is not a job for amateurs because you have only one chance to get it right. Many excellent works of art have been lost to well-meaning but destructive cleaning attempts.

There is no one-size-fits-all formula for removing accumulated grime, discolored varnish, and old restoration from a painting. Every painting is a unique object that can be dramatically different from others as a result of artist’s technique, materials, age, past restoration, and the effects of time and environment. A cleaning treatment has to be tailored to the unique demands of the object itself. Any number of cleaning substances might be used, alone or in combination, including: water, organic solvents, surfactants, chelators, enzymes, acids, and bases. In a few cases when no liquid can be used, only mechanical cleaning using erasers, sponges, or scalpels is deemed safe and effective. Usually a skilled and experienced conservator can remove grime, varnish, and old restoration. But there are instances where an object cannot be cleaned without possibly damaging original materials. If the risk of damage is deemed too high, then no cleaning attempt is undertaken.

The cleanest hands have a coating of perspiration, which can damage works of art. Fingerprints can etch into metal. Stone, textiles, and wood are porous and absorb dirt and oil. Marble and bronze are especially susceptible to staining and discoloration from human touch. Paint is often brittle, and a finger placed against a painted surface easily causes damage. Over the years the Conservation Center has attended to many works of art damaged by vandalism or inadvertent contact—for example, blood stains on the Milton Avery Blue Landscape; bubble gum on the Eugene Berman Sunset; barbecue sauce stains on the Morris Louis Pi; and various scuffs, scratches, fingerprints, and smudges on numerous paintings. The most endearing damage was a child’s small green handprints placed over the ankles of George Washington on the Roger Brown painting American Landscape with Revolutionary Heroes. The child’s hands were green from climbing just moments before on the pollen-covered Henry Moore sculpture Spindle Piece outside.

Various systems are in place in our Museum to protect the art, including the ever-watchful eye of the security guards or security camera, protective stanchions, display cases and cabinets, and security glazing. When you come to the Museum, we encourage you to enjoy the richness of our collection—just don’t touch it!

You may wonder why one work of art is glazed or placed behind stanchions, while another is not. We can’t glaze everything. By practical necessity we are selective, picking those works of art that are in a vulnerable location, exceptionally valuable, seem to attract undue attention, have condition problems, or where relatively minor damage could be irreversible, such as the stain on the unprimed canvas of our Morris Louis. (There was a recently reported case of gum stuck on a Helen Frankenthaler painting at the Detroit Institute of Arts that left a stain.) We try to strike a balance between securing the collection and providing the unfettered access people enjoy and expect.

Over the past several years we have taken a more proactive approach to protecting the art, identifying about 50 paintings for glazing based on the above criteria. Glazing a painting involves installing it in a frame behind a protective material such as glass or acrylic sheeting to protect the surface from harm. Because the glazing stands between you and the painting, it can interfere with the quality of your viewing. To minimize this negative effect, a high-quality security glass is chosen. This specialty product is low iron, antireflective, and laminated. It is engineered specifically for works of fine art to enhance, preserve, and protect the art on display. But the price for quality is high.

Security glass has been installed on a painting by Pieter Aertsen—A Meat Stall with the Holy Family Giving Alms—an exceedingly important and valuable 16th-century still life. On examination, dozens of fingerprints were detected on the surface of the painting, primarily over the flayed ox head and pig carcass. Perhaps people were responding to the graphic reality of the display of meat, perhaps touching it to make it real. Properly lit in the gallery, the glass is almost undetectable, allowing for optimum viewing.

Various systems are in place in our Museum to protect the art, including the ever-watchful eye of the security guards or security camera, protective stanchions, display cases and cabinets, and security glazing. When you come to the Museum, we encourage you to enjoy the richness of our collection—just don’t touch it!

In most cases, no. (We should keep in mind that this point refers to freestanding or easel paintings dating from the 16th through the 20th centuries.) One consistent reality of these paintings, along with their frames, is that they have frequently changed ownership. They have been willed repeatedly through a family line, or sold, traded, or stolen. The one sure stamp of ownership one can exert on a new possession is to change the frame—and so this was done frequently. On occasion the frame change was made solely to “clean up” the overall appearance. In the best cases, the old frame was simply stored in an attic or basement. In all too many cases, the offending article was simply discarded, as the concept of frame conservation or restoration is relatively recent.

Museum framings are a display of the results of many centuries of changing ownership and sense of style or decoration. We see today on the walls of a majority of the world’s fine art museums only the most recent attempts to pair paintings with their appropriate frames.

Curatorial priorities largely govern the scheduling of projects, although it is understood that treatment priority will be given where a project requires immediate attention. Works of art scheduled for loan or exhibition may require preparation to ensure travel readiness or may need restoration for improved appearance. The scheduling of treatments is a collaboration between the two departments, with priorities reviewed and updated annually.

Museum framings are a display of the results of many centuries of changing ownership and sense of style or decoration. We see today on the walls of a majority of the world’s fine art museums only the most recent attempts to pair paintings with their appropriate frames.

Conservation treatments can be highly variable in their scope, and treatment time varies widely. A small painting that requires only removal of a light grime accumulation may take only a few hours. The full treatment of a large Old Master painting with multiple layers of old varnish and restoration, possibly requiring major structural work on the stretcher or canvas, can take a year, two years, or more. Treatments always include written and photographic documentation, as well as discussion between the conservator and curator.