Mummies, gold, and an obsessive belief in the afterlife.

These ideas are at the core of our interpretation of “Ancient Egypt.” But how important were these concepts to the Egyptians, and how long did they survive after the last of the pharaohs? Golden Mummies of Egypt uses the outstanding collection of the Manchester Museum in England to explore expectations of a life after death during the relatively little-known Greco-Roman era of Egyptian history—when Egypt was ruled first by a Greek royal family, ending with Queen Cleopatra VII, and then by Roman emperors (a period spanning 300 B.C.E.–300 C.E.).

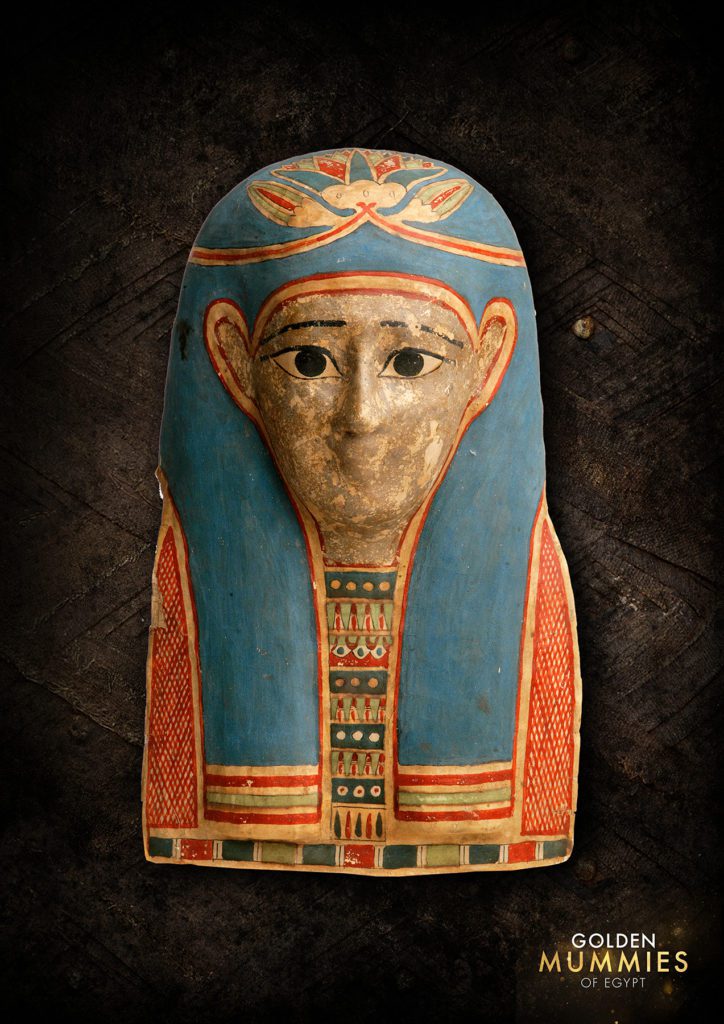

Greeks and Romans had rather bleak expectations for an existence after death. However, the Egyptian afterlife offered them the possibility of being reborn into a bright, perfected version of this world, to join Osiris, the god of rebirth and ruler of the underworld, and to live for eternity. Wealthy members of this multicultural society made elaborate preparations for the afterlife, combining Egyptian, Greek, and Roman ideals of eternal beauty. The millennia-old sacred art of mummification was still practiced, but the coffins that protected the mummies had largely fallen out of use. Instead, intricately wrapped mummies were decorated with images of Egyptian funerary deities and amuletic symbols that offered protection against the various dangers on the path to the afterlife as well as hauntingly beautiful portraits or arresting plaster or cartonnage mummy masks that gave the deceased the power of sight.

Made of painted and gilded cartonnage—which is like papier mâché—the mummy masks are not meant to hide or obscure the face of the departed, as the word mask implies. Instead they are representations of the deceased, eternally beautiful and idealized, shown with characteristics of Egyptian deities said to have skin of gold and hair of lapis lazuli (a blue, semiprecious stone). Resembling a deity was a powerful aid to achieving eternal life, as gods in Egypt were thought to be immortal. Gold’s glittering quality also symbolized the reflection of the sun’s rays and was associated with the sun god, Ra, who was reborn every morning. Thus the act of covering an object in gold was thought to provide magical protection.

Pharaonic mummy masks were just the start. Linen shrouds, plaster or cartonnage portraits, and wooden mummy panels depicted the deceased with Roman hairstyles, garments, and jewelry fashionable at the time. Of these, the mummy panels—the so-called Faiyum portraits—are among the most striking images from antiquity. Each was made using a mixture of hot wax and pigment, creating a stunning, lifelike effect that appeals to modern tastes.

Golden Mummies of Egypt presents eight mummies, all retaining their original portraits and mummy coverings, fully wrapped and untouched since antiquity, and some still in their coffins. The mummies were discovered at Hawara, Egypt, in 1888–89 and 1910–11 by the famed British Egyptologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie. However the exhibition is much more than just mummies and their beautiful, idealized portraits; the show places Egypt within a broader ancient Mediterranean context and its ties to Nubia, explores religious beliefs and expectations for the afterlife during this multicultural period in Egypt’s ancient history; discusses the practices of preservation and decoration of the body, and the transformation of the deceased into a divine being; introduces social constructions of identity; and puts the archaeological excavations at Hawara in their colonial and sociopolitical contexts.

Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design

Academy Award–winner in Costume Design, Ruth E. Carter has helped bring characters to life in acclaimed Hollywood blockbusters. The NCMA celebrates the magic of her imagination.

Innovative AIM Program Reaches Thousands

Thinking outside the lines, NCMA outreach programmers connect local artists in rural communities with local students excited to discover the artist within.

Love in the Galleries

This Valentine’s Day we invite you to follow Cupid’s arrow through West Building to discover some amorous works in the NCMA’s collection.