Ann and Jim Goodnight Museum Park

Choose your own adventure in the Museum Park. Picnic with family and friends. Engage in bird watching on a trail. Walk, bike, or run on the Capital Area Greenway. Enjoy the beauty of native plants and sounds of wildlife in the midst of bustling Raleigh. Discover art, nature, and people through both self-guided and facilitated experiences. Get comfortable, linger, and belong.

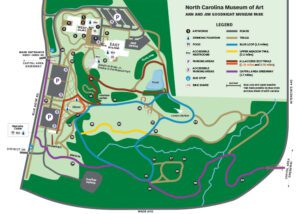

The Museum Park features both permanent and temporary art installations, environmentally sustainable landscapes, colorful and contemporary gardens, 4.7 miles of recreational trails, and a terraced pond. To learn more about how we are always evolving, visit our 2021 Museum Park Vision Plan.

Art in the Park

The Museum Park art program facilitates collaborations among artists, designers, and environmental scientists to create works of art inspired by the natural world. Artists are commissioned to create site-specific temporary and permanent works that directly engage the landscape and present new perspectives on the natural world, exploring our relationship to the environment and the role of nature in contemporary society.

Park Information

- The Museum Park is open free to the public from dawn to dusk.

- Welcome Center restrooms are open daily dawn to dusk. Food and retail hours are seasonal, with the current hours of Wednesday–Sunday, 10 am–5 pm.

- A Cardinal Bikeshare kiosk is located at the Reedy Creek Road entrance. Rent a bike to ride the paved trails.

- Bus stops are located at both Reedy Creek Road and District Drive entrances. See the Go Raleigh Blue Ridge Road Bus Schedule.

- Bike or walk to the Museum Park via the Capital Area Greenway.

- Construction and trail closures:

- Work is underway in the southeast corner of the Ann and Jim Goodnight Museum Park as part of the I-440 improvement project. All work is taking place in the right-of-way and not on Museum Park property. The project is expected to be completed in the fall of 2022. If you have any questions, please visit the NC Department of Transportation website.

- The DHHS, COR, and DOT will begin work along Blue Ridge Road effective August 2022, ending in 2025. We will do our best to provide updates of major disruptions as we know of them. We look forward to these positive contributions planned for the Blue Ridge corridor.

NCMA Park App

Explore featured art, nature, and campus history tours, audio descriptions, GPS navigation of the Museum Park, and more. Learn about the NCMA Park App here.

All-Access Eco Trail

The All-Access Eco Trail is designed using integrated access to enhance visitors’ experiences of the Park’s native plants, wildlife, and habitats.

Each stop on the trail features audio-described stories about the Park’s natural features and sensory exploration prompts paired to each sign. The signs include large print, braille, and touchable images. On the bottom left side of each sign is a mini-map that displays the path to the next stop.

The trail consists of two options that both begin at the Welcome Center. The longest route is approximately three-quarters of a mile in one direction and contains 13 stops that conclude at the Park’s pond. For a shorter experience, follow three signs that end at the Ellipse. This route is wheelchair accessible and approximately one-quarter of a mile on paved, mostly level pathways.

Access the Eco Trail audio descriptions on the NCMA Park app, available from Apple’s App Store and at ncmapark.org (web version for Android), or on SoundCloud.

Birds of the Museum Park

Make connections between art and nature with this checklist of birds that have been observed, seasonally, in the Museum Park.

Endangered Species

Celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) (fws.gov/law/endangered-species-act) with this scavenger hunt!

Scavenger Hunt

Explore the Museum Park through the Art + Nature + People scavenger hunt. This interactive activity takes you throughout our 164-acre Park and encourages creative experiences and human interactions for all ages. To use, download the PDF, grab a hard copy from the Museum Park Welcome Center, or request one from our Park rangers when you visit.

Recreation

The Museum Park has 4.7 miles of recreational trails that lead visitors through natural areas to commissioned works of art. Trails in the Park are made of both paved and unpaved surfaces. Designed for hiking, walking, and jogging only, the unpaved natural trails allow visitors to deeply experience art and nature. Cyclists and self-propelled wheeled vehicles may travel on paved trails only. The Capital Area Reedy Creek Greenway system is a paved multi-use pathway that runs through west Raleigh and connects the eastern portion of the Park, Meredith College, North Carolina State University, and downtown Raleigh via the pedestrian bridge over 440. In the opposite direction, the Greenway exits from the Park and continues to Umstead State Park.

Park rules protect visitor safety, works of art, and the environment.

Public Safety

- It is unlawful to possess firearms or other weapons on Museum grounds.

- Fireworks, cap pistols, air guns, bows and arrows, slingshots, and lethal projectiles of any kind are strictly prohibited.

- Possession or consumption of alcoholic beverages is prohibited except during Museum-organized events.

- Drones or other mechanical flying devices are prohibited.

- Unauthorized motor vehicles are prohibited on Park trails.

- Overnight camping, charcoal grills, and fires are prohibited.

- Gatherings in the Park cannot involve the use of confetti, paper poppers, etc.

Bikes and Pets

- Cyclists and skateboarders must yield to pedestrians and be courteous of other trail users.

- Cyclists should give an audible signal when passing.

- Speed limit for trail users is 10 mph.

- Pets must be on leash.

- Owners are required to clean up after their pets. Deposit pet waste in available trash receptacles.

- Owners may be asked to remove aggressive or noisy pets.

Art and the Environment

- Do not climb on or touch works of art in the Park, unless otherwise indicated, and stay on trails.

- Do not disturb natural areas. Removal or injury of any plant in the Park is prohibited.

- Carry all trash to a receptacle or out of the Park.

- Metal detectors are not permitted.

- Commercial business activity, including photography and video recording, is permitted only with prior authorization.

- It is prohibited to remove, destroy, or damage plant life or property.

- It is prohibited to kill, trap, or harm wildlife.

Discover More

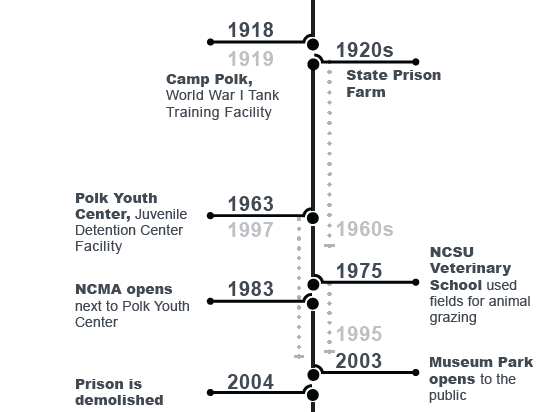

The Museum Park has been transformed over the last 40 years, since the Museum opened on Blue Ridge Road in 1983, growing from the original 50-acre site to the current 164-acre campus of trails and outdoor sculpture. The Park provides a unique opportunity for active living amidst art and nature.

Welcome Center

The Museum has redesigned an underutilized portion of the Park to welcome visitors at the District Drive entrance. Intentionally transformed from a former place of imprisonment into a welcome zone, it invites fun and exploration. The Welcome Center provides comfort with water fountains, food, and restrooms. Visitors of all ages can enjoy the Musical Swings and Daydreamer Benches. A sunflower field planted behind Wind Machine delights visitors, pollinators, and birds each fall. The patio beside the smokestack provides a gathering place for friends and family. Learn more about architecture at the Museum.

Sustainability

Sustainability measures can be found throughout the Park. Wildlife is supported by a diverse palette of native plants, and habitats are preserved through invasive species management. Stormwater runoff is captured from the landscape, buildings, and parking lots and filtered for pollutants, improving water quality and preventing flooding downstream. The system also filters runoff through terraces of native plants and soil before it enters the pond. The pond is part of a water conservation system that includes a 90,000-gallon underground cistern used for the water features and irrigation system around West Building. Learn more about sustainability and stormwater management in the Park.

Habitats

There are many habitats in the Park that create an ecosystem that supports the preservation of native plants, birds, insects, reptiles, and amphibians. The ongoing restoration of the Park manages forests, prairies, a pond, and streams. We invite you to explore the pond, the most active area for wildlife viewing. Rest on the pond platform and experience the largest element of surprise and delight in the Park. Learn more about the various habitats in the Park.

History of the Land

While no American Indian sites have been identified within what is now the Museum Park, since the area encompasses a creek, it is probable that American Indian activity occurred here. From 1920 to 1997, North Carolina operated a prison farm and correctional institution on the property. The Polk Youth Detention Center was relocated to Granville Correctional Institution in 1997; the buildings were removed in 2004. In 2001 the Department of Transportation created an extension of the Capital Area Greenway through the area. The Park first opened to the public in 2003. Learn more about the history of the site.

Natural History

The Park is located within the Northern Outer Piedmont ecoregion and is part of the Upper Neuse River Watershed. For over 160 years, the majority of the site was converted from its natural forested condition into various land-use types. The clearing of the oak-hickory forest and conversion to agriculture had severe and long-lasting effects. The removal of trees led to the destabilization of topsoil, which increased stormwater runoff and sediment deposition into the streams. Agricultural use also caused a reduction in the diversity of plant life and wildlife. Learn more about what the Museum is doing to reverse negative impacts to the Park site.

Joseph M. Bryan, Jr., Theater in the Museum Park

PICTURE THIS

The Museum’s Amphitheater is part of a large-scale environmental artwork by two architects, an artist, and a landscape architect (designed 1992–94, constructed 1994–97). Integrating art and architecture, the work is built around the phrase PICTURE THIS. The giant letters are sculpted in various materials and cover over 2 1/2 acres. Many of the letters incorporate text with specific references to the history, culture, and landscape of North Carolina. The space welcomes 50,000+ visitors annually to enjoy music, film, and the performing arts. Learn more about Picture This and performances in the Amphitheater.