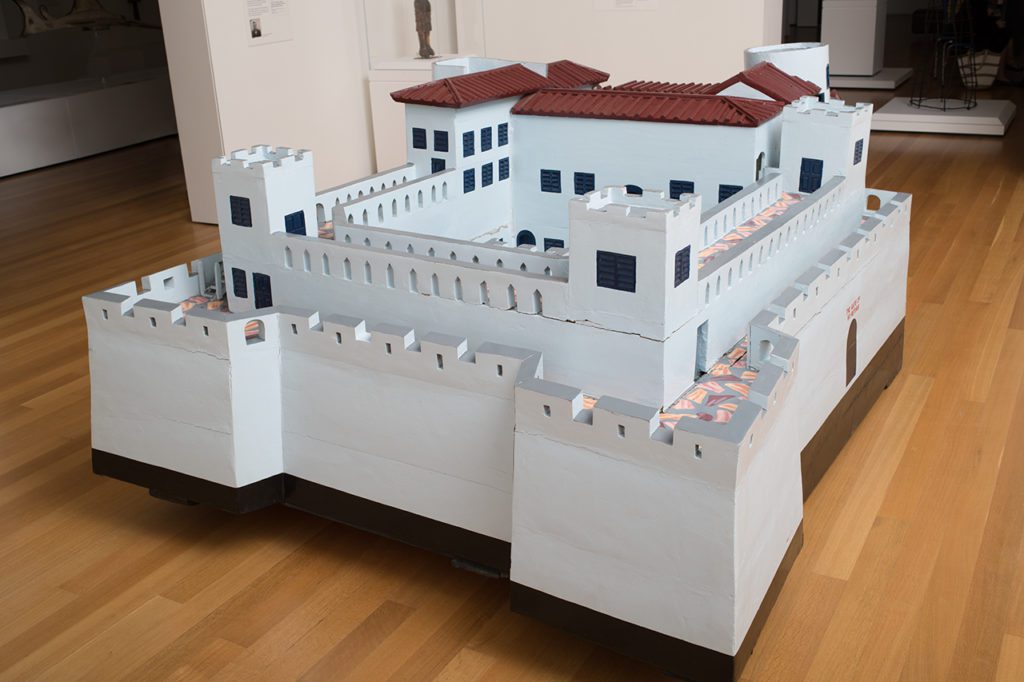

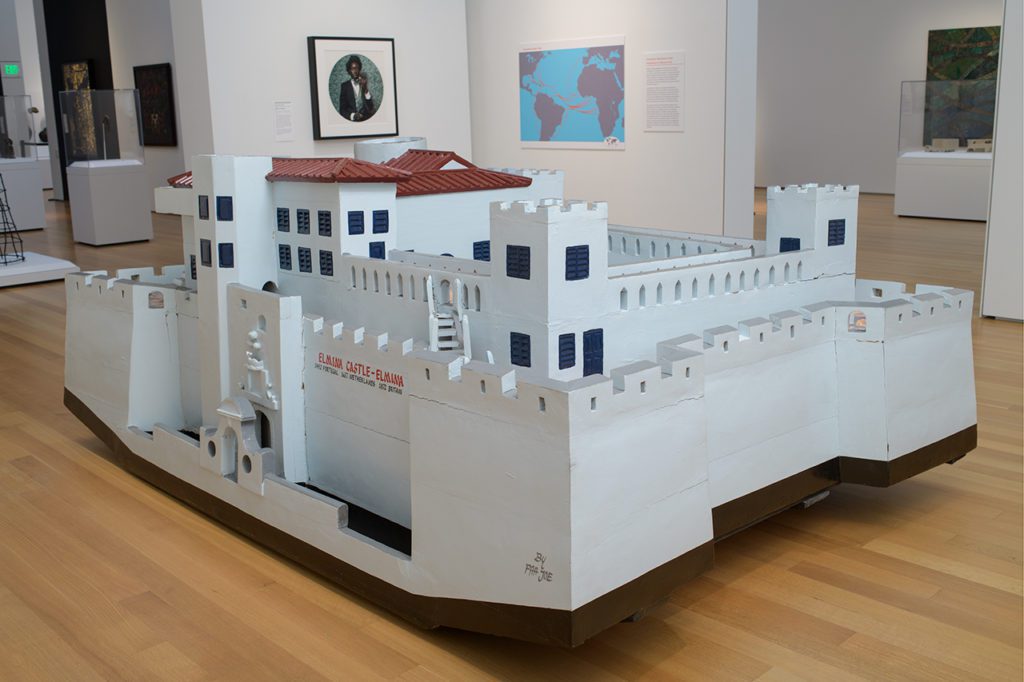

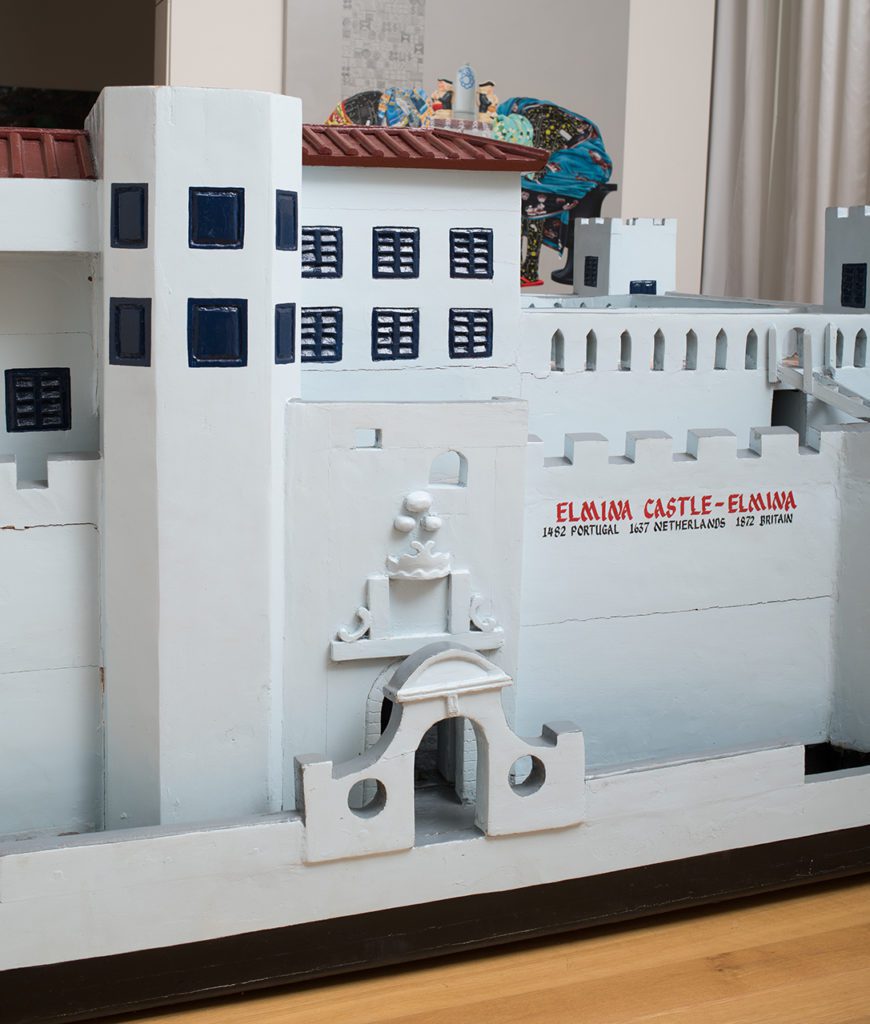

From 2004 to 2005, artist Joseph Tetteh Ashong, popularly known as “Paa Joe,” crafted and painted 13 large-scale sculptural representations of castles and forts integral to the transatlantic slave trade, built and used between the 15th and 18th centuries and which dot the coast of present-day Ghana. He created these miniature but mighty replica fortresses using the same techniques he used in his widely celebrated “fantasy coffins,” or custom figurative coffins. These fantasy coffins creatively honor deceased individuals in larger-than-life fashion. Often symbolizing the character and accomplishments of the recently departed, they can range in shape from chickens, lions, fish, and eagles to cell phones, paint brushes, sneakers, airplanes, and even beer or whiskey bottles. Recently acquired by the North Carolina Museum of Art, Elmina Castle is one of Paa Joe’s original 13 slave fort replicas. While not fantasy coffins per se, these historical sites are death vessels in their own right, and Paa Joe’s memorial models—scaled to the size of a human body—serve as a powerful reminder of where the perilous journey into slavery began, as two NCMA staffers explain:

Marion Tisdale IV, Visitor Experience Associate

When I began interning at the NCMA, I didn’t know Elmina Castle by name. I didn’t know who built it, or how many more castles there were just like it. I did know what “The Gates of No Return” were: that they were the last physical contact enslaved Africans would have of their homeland before the trial that was the Middle Passage.

I then knew only broadly, indirectly, of Elmina and many others, as encompassed within the phrase “The Gates of No Return” and as a hellscape where the unspeakable happened. I knew that the genesis of my ancestors’ suffering and countless others began at those castles. It is not insignificant when an oppressed people acknowledge the trauma a space holds rather than its name. It is ironic to even dwell on the naming of the castle, given that the slavers who ran Elmina made sure that the Africans who went through its walls and bars would remain nameless. Erased, dehumanized, and treated like cargo, those who endured Elmina and were subsequently lost were not regarded highly enough to consider the importance of their lineage and ancestry—to consider their names.

In spite of the countless attempts to scrub the Africans who survived Elmina, the castle has now become a space for memorial. Thousands upon thousands of African Americans visit Elmina and the many others like it every year as a way to give homage to their ancestors.

While we may not know the names of those lost, we can still honor them. We can still remember them. This may seem insignificant, but I argue that by making the pilgrimage back to the “Gold Coast,” we are giving back the humanity that was systematically stripped from our ancestors.

This is an act of revolution.

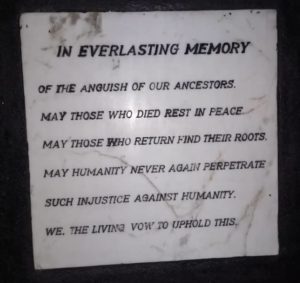

May humanity never again perpetrate such injustice against humanity. We, the living, vow to uphold this.

—Excerpt from memorial plaque at entryway of Elmina Castle

In addition to these trips of remembrance, artists have found ways to give homage through creative acts, and still others have the opportunity through this art to return emotionally rather than physically. Paa Joe, a pillar in the Ghanaian art scene, first came to fame as a “fantasy coffin” maker. If you haven’t heard of a fantasy coffin before, imagine a loved one, and then what they in turn loved most in the world. What encapsulated them in life? It could be photography, cooking, motherhood, or even something as simple as a can of Pepsi. Now imagine their coffin being modeled after that love: your fisherman uncle gets buried in a fish-shaped coffin; your cousin who adored singing or was a professional musician is now laid to rest in a giant microphone.

These individualized acts of love and remembrance are what Paa Joe, along with his son and apprentices, specializes in. Like his artwork Elmina Castle, these are memorials that offer people the opportunity to remember their loved ones in a meaningful way. In an American context, many may forget that to be “properly” buried is a privilege. As the last rite, it is a right that belongs to everyone. To intentionally and systematically disrupt that right—as happened during the transatlantic slave trade—is to attack even the smallest shred of personhood and dignity.

These individualized acts of love and remembrance are what Paa Joe, along with his son and apprentices, specializes in. Like his artwork Elmina Castle, these are memorials that offer people the opportunity to remember their loved ones in a meaningful way. In an American context, many may forget that to be “properly” buried is a privilege. As the last rite, it is a right that belongs to everyone. To intentionally and systematically disrupt that right—as happened during the transatlantic slave trade—is to attack even the smallest shred of personhood and dignity.

Such expertise in the act of memorialization gives Paa Joe one of two very keen points of view: that of a coffin maker whose work deals in providing a way to remember those we have lost and also that of a proud Ghanaian man. When dealing with the atrocities of enslavement, we don’t often talk about the losses felt from the continental parts of the diaspora. Consider the fact that there are so many castles like Elmina (many are featured in The Gates of No Return series) that one can be found every seven and a half miles. Such fortresses were made to symbolize and solidify European authority on African land and did not consider or include the losses that were felt from those shipped off and those left behind as a result.

Paa Joe activates a space where Black bodies were robbed of agency, and in this way he names the nameless and returns this agency to the dead. As a Black man, I find that my most reliable connection to my African ancestry are the spaces that were meant to destroy my forefathers. There are names I will never hear and never speak, but there are spaces where I can acknowledge them, and show the fruits of their labor through my survival.

Amanda M. Maples, Curator of Global African Arts

Paa Joe’s Elmina Castle, when viewed from the front or back, curves gently up on both sides, mimicking the shape of the ships that carried the bodies—by force—to the Americas. Paa Joe represents such histories not only in the painstaking re-creation of these sites of trauma, but also by recording the Anglophone names and histories of colonial “ownership” in the title, Elmina Castle—Elmina (1482 Portugal – 1637 Netherlands – 1872 Britain), and painted in red over each model’s doorway. This practice reminds us that this history—while culturally embedded within the walls—may not be visible and that artists can reveal what might be otherwise obscured. The infamous “Gate of No Return” is similarly painted in red above each of the back doors. These doors opened directly to ship and sea and were often the last glimpse of the continent that enslaved humans had.

Of the 13 forts, Elmina Castle is the most visited by African Americans and gives a powerful access point for exploring the traumatic histories that have shaped the development of the Americas since the 18th and 19th centuries. Though often not as visible, the legacies of slavery and racism remain, and Elmina Castle presents a provocative commentary particularly relevant in the wake of nationwide protests regarding racial equity and social justice.

Meet Thomas Sayre

The NCMA’s new identity and logo were inspired by an iconic sculpture in the Museum Park. Get inside the mind of the Raleigh artist who created Gyre.

The Africa We Ought to Know

In the past the fusing of diverse beliefs and practices was widespread and remains a constant feature of African culture today.

The NCMA’s New Visual Identity

The North Carolina Museum of Art’s new logo takes as its inspiration an iconic sculpture in the Museum Park and a visitor favorite.