Featured in the NCMA’s Meymandi Exhibition Gallery through January 22, 2023, A Modern Vision: European Masterworks from The Phillips Collection promises “a masterpiece around every corner,” as curator Michele Frederick said when I sat down with her to discuss the show.

What are some of your favorite works in A Modern Vision?

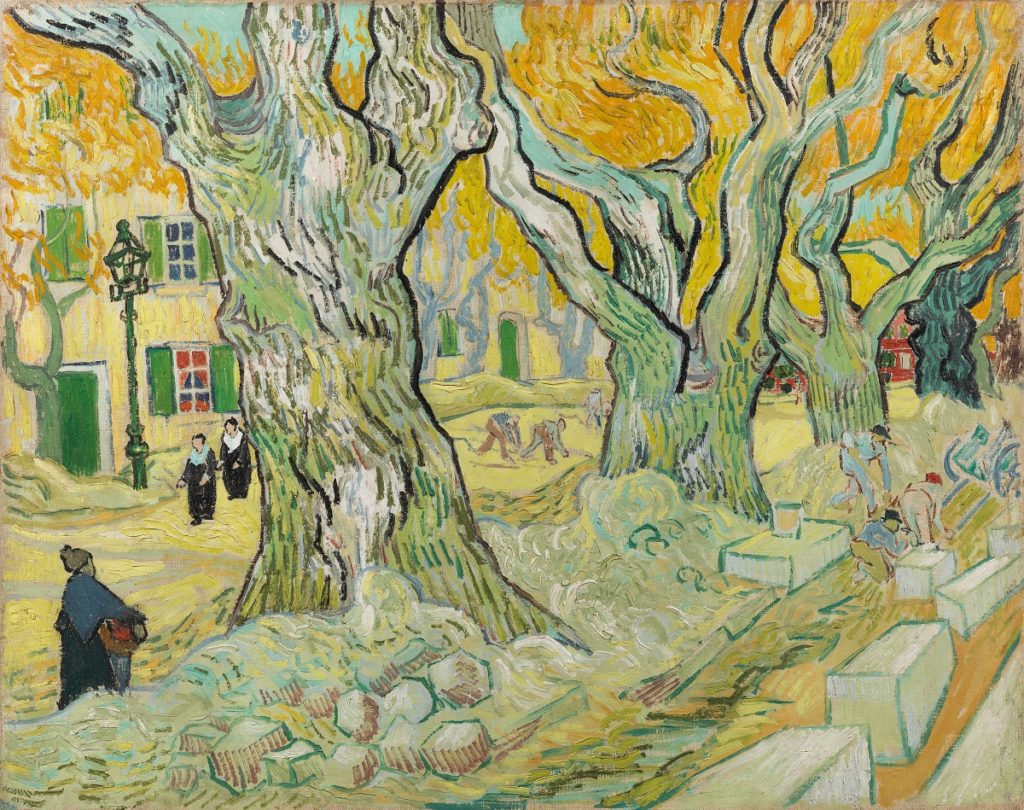

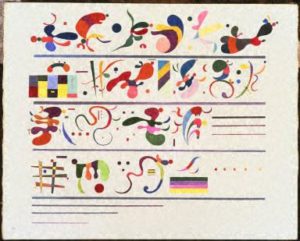

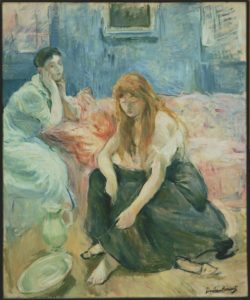

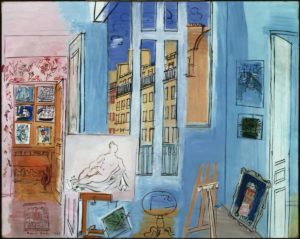

It’s so hard to choose—it feels like there’s a masterpiece around every corner! I love the color and brushwork in Paul Cézanne’s Ginger Pot with Pomegranate and Pears (1893), the quiet intimacy captured by Berthe Morisot in Two Girls (1894), the amazing patterning of Pierre Bonnard’s The Riviera (circa 1923), the lyricism of Wassily Kandinsky’s Succession (1935), the colors of Raoul Dufy’s The Artist’s Studio (1935), and, of course, everything about Vincent van Gogh’s The Road Menders (1889).

Which painting might slip by the casual visitor that you think shouldn’t be missed?

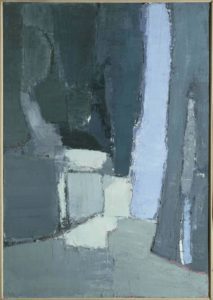

Nicolas de Staël’s Le Parc de Sceaux (1952) and Paul Klee’s Tree Nursery (1929). The De Staël is tucked around a corner but has some of the most enthralling texture I’ve ever seen—plus it’s larger than a lot of the other paintings in the show, so it really has presence. The Klee, on the other hand, is quite small and tends to get overshadowed by the large Georges Braque still life hanging next to it. Like many of the paintings in the exhibition, it really benefits from getting up close to take in the texture and details, and I just love looking at it!

In a tour you mentioned the terrific lighting and installation of this show. Can you share what you love about it?

The design of the exhibition, from the arrangement of the walls to the choice of paint colors, really reflects and pays homage to the domestic space of the Phillips Collection galleries, which are in the Phillips family’s former home in Washington, DC. It also encourages an intimate experience with these works of art that I feel like Duncan Phillips would have appreciated, and it encourages our visitors to meander through the galleries at their own pace.

Likewise, lighting is key to bringing these works to life. Our lighting designer, Amber, did an amazing job at making the paintings glow and stand out from the walls in ways the artists themselves probably couldn’t have imagined. The lighting throughout the exhibition emphasizes the intimacy of the design and draws visitors to one stunning painting after the next! Huge shout-out to Mary Wolff, our chief exhibition designer, and Amber Smith, our lighting designer, for all their amazing work on this show.

What was it like for women to be painting during this period? Did many collectors want work by women?

Especially in the 19th century, when many of the earlier works in this exhibition were painted, it was incredibly difficult to be a female artist. In the French context, where a number of the artists in the show were born or worked, women were not allowed admittance to the official French Academy of Arts until 1897. This made it incredibly difficult to be trained as an artist and to publicly exhibit your work in the official Salon Exhibitions, which presented a challenge to women wanting to be professional artists.

Around the turn of the 20th century, these systems started to become more egalitarian, but women still faced a male-dominated art world that had been systematically excluding them for hundreds of years. Works by female artists are consequently under-represented in museum and private collections (of 52 paintings in this exhibition, for example, only three are by women). Some collectors surely were less interested in acquiring works by women, but these artists started at a deficit in that there were fewer of them able to enter the field and therefore fewer works available to collectors in the first place.

What can you tell us about the amazing frames on many of the paintings in A Modern Vision?

A number of people have asked me about the frames throughout the show—which are diverse works of art in and of themselves and have attracted a surprising amount of attention. The biggest question is whether the frames are original, and this is a complicated one to answer. Many of the frames in the exhibition are not original to the paintings in that they weren’t made at the same time as the paintings or specifically for them, but in most cases they are older frames put on either by the artists or their dealers in order to make the more modern-looking paintings seem a little more traditional and appeal better to buyers. In the case of the more modern-looking frames on the paintings made by artists who were living at the time Phillips was collecting, in most cases those frames would have been selected or made by the artist or dealer specifically for those paintings. In most cases I think the frames are the same as the ones that were on the paintings when Phillips bought them, so none are modern reproductions and in that sense are all “original.”

A Studio of Their Own

Art historian Alexis Clark draws a sharp distinction between two very different artists’ studios, in the same city, four decades apart.

Sneak Peek: A Modern Vision

A Modern Vision opens with works by some of the titans of impressionism, postimpressionism, cubism, and expressionism.