New thematic galleries that are part of Reimagining the People’s Collection broaden representations and narratives within the Museum. In the reinstallation the ancient Egyptian collection is adjacent to the galleries of African arts. Connecting them is The Africa We Ought to Know, an exciting new interpretive space. I asked two curators to describe artworks they are excited to reimagine in this new gallery.

Caroline Rocheleau, Curator of Ancient Collections

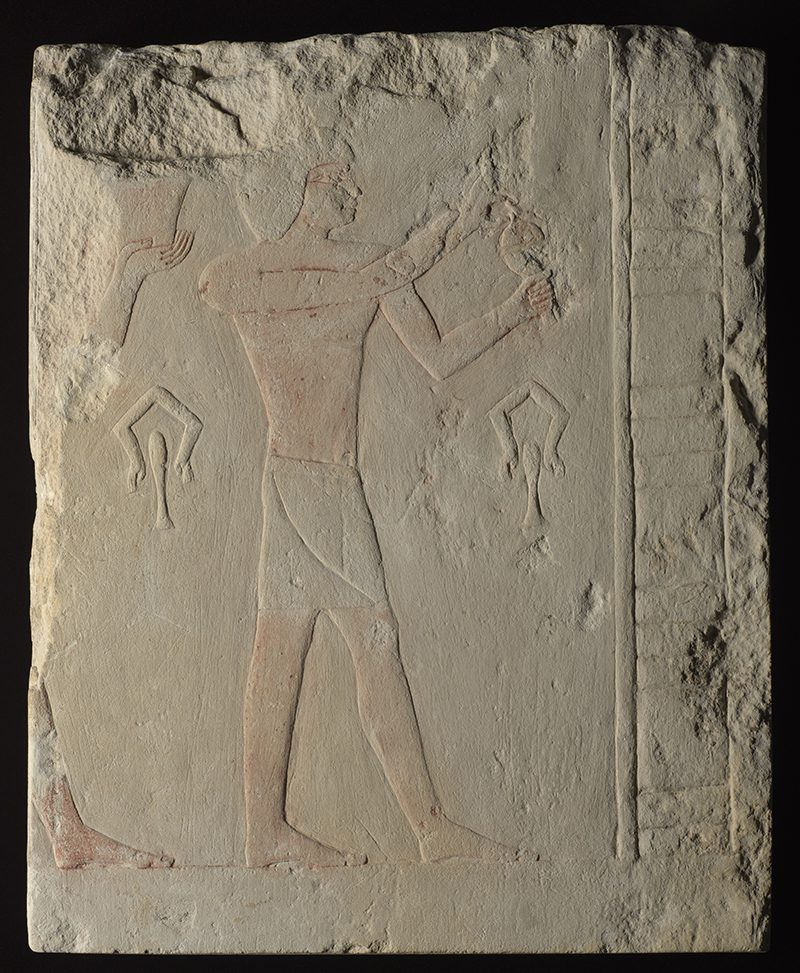

The multiplicity, diversity, and interconnectivity of religious practices on the continent is one of the themes explored in The Africa We Ought to Know. Relief Fragment Featuring a Ka Priest expresses ancient Egyptians’ keen awareness of human fallibility. The deceased’s survival in the afterlife rested partially on the integrity of the ka priest (servant of the soul), who brought daily offerings to feed the departed’s ka. Carved images and associated hieroglyphs were imbued with such power that their presence on tomb walls ensured that provisions were magically offered, should all else fail.

Amanda M. Maples, Curator of Global African Arts

Similarly, a 20th-century Coptic Christian icon incorporates the power of words and images. Above the cross a triangle symbolizing the Holy Trinity features the eye of Horus (Ra?)—a powerful protective symbol in ancient Egypt. Given Christian symbolism of the all-seeing God, it is fitting imagery. Figures are identified in Arabic, and the name of the hill upon which Jesus stands—Golgotha—is visually indicated. In both Latin and Aramaic, Golgotha means skull. This blending of languages and iconography highlights global connectivity. The fusing of diverse beliefs and practices remains a constant feature of African culture today.

See more objects in this gallery on NCMA Learn.

Naming the Nameless

Ghanaian artist Paa Joe memorializes the lives of Africans who passed through “The Gates of No Return” during the transatlantic slave trade. Two NCMA staffers respond to this moving work of art.

Meet Thomas Sayre

The NCMA’s new identity and logo were inspired by an iconic sculpture in the Museum Park. Get inside the mind of the Raleigh artist who created Gyre.

The NCMA’s New Visual Identity

The North Carolina Museum of Art’s new logo takes as its inspiration an iconic sculpture in the Museum Park and a visitor favorite.