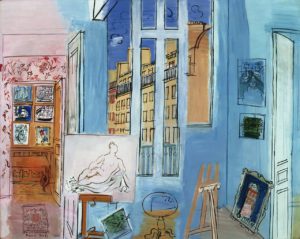

The NCMA’s newly acquired painting Mon Atelier by Lucie Attinger (1889) takes on added meaning when compared to a striking but very different painting by Raoul Dufy, The Artist’s Studio (1935), on display in the special exhibition A Modern Vision: European Masterworks from The Phillips Collection (open now through January 22, 2023).

Only in 1897 were women artists admitted to Paris’s prestigious École des beaux-arts. Restricted due to their sex but also subject to moral strictures on seeing nude models, women artists instead enrolled in one of the many private ateliers and studios in Paris, including the Académie Julian, the setting for Lucie Attinger’s painting. Opened in 1867, the Académie Julian would be key to late-19th-century women artists’ equality in education, exhibitions, and acknowledgment. The Swiss Attinger and her fellow female art students from around the world flocked there to receive crucial opportunities to study models and to learn from celebrated male artists—an important education for those seeking to produce grandes machines, or large-scale paintings of episodes from the bible, classical mythology, and history.

Painting such subjects with their large casts of heroes and villains required artists to work with many models like the shaggy, slumped, bearded male model shown here. With the notable exception of Attinger, whose steady gaze meets ours, the other female students at the Académie Julian all turn their attention to this model. As these women worked, their male teachers offered advice and correction. Accordingly, Attinger depicts the hand of the central female student met by the hand of a hidden figure. While this hand may belong to one such male teacher, the hint of a gray skirt suggests the hand to be that of another female pupil. Without the education afforded by places like the Académie Julian, 19th-century women artists were frequently limited to painting flowers and fruit or intimate circles of family and friends, or to making decorative arts and domestic crafts, which were not recognized as “high art” in the 19th century.

Four decades later, Raoul Dufy painted his own atelier in Montmartre. The Artist’s Studio surveys the contents of his workspace: unframed sketches tacked to a side wall, a framed painting of a multistory home propped against that same wall, an empty wooden easel, an artist’s palette on a tilted tabletop, and a hallway wall papered in a floral pattern on which a double row of still more marine paintings hang. A painting of a nude—striking a pose typical in rococo scenes such as Venus Rising from the Waves by François Boucher—occupies the center of Dufy’s composition between a pink hall and blue studio walls. The nude possesses a certain muscularity, even strength. Their thick arms and legs and relatively small breasts mark a break with the rippling rolls of soft flesh caressingly brushed by Boucher. Dufy’s outlined forms, thin washes of paint, and overall decorative, stenographic style led to his collaboration with fashion designer Paul Poiret. Yet, for much of the 20th century, stenography was associated with (often female) secretaries using shorthand notes to speedily record information dictated by (often male) supervisors. By choice or by necessity, women pursued clerical education to work outside the home.

While having a home office and studio clearly bolstered Dufy’s creativity, Attinger’s title declares the Académie Julian her studio and so her creative space: Mon Atelier. My studio. How do paintings like these scramble associations commonly made among gender, creativity, and space? What does it mean to have a creative space of one’s own?

A Modern Vision: Curator’s Picks

Circa drops by the desk of NCMA curator Michele Frederick to get her take on A Modern Vision, a show so full of masterworks, it’s hard to find a favorite.

Sneak Peek: A Modern Vision

A Modern Vision opens with works by some of the titans of impressionism, postimpressionism, cubism, and expressionism.