If the role of contemporary art is to act as a mirror for society, then two significant exhibitions at the NCMA and SECCA paint a picture as beautiful as it is unsettling.

As its name implies, Fault Lines: Art and the Environment explores humanity’s relationship to the environment through an immersive, multimedia exhibition and outdoor sculpture installations. A group exhibition of 14 contemporary artists from around the world, the NCMA’s Fault Lines examines urgent environmental issues, consequences of inaction, and opportunities for sustainable environmental stewardship and restoration.

In SECCA’s Main Gallery, Diné (Navajo) photographer and community engagement artist Will Wilson addresses institutional racism and Indigenous futurism with Connecting the Dots, a mid-career retrospective showcasing photography and sculpture.

At first glance the two exhibitions appear to operate in different spheres. But parallels emerge in the aerial photographs on view in both. In two particular images, vibrant colors and textural terrain lure visitors in with a breathtaking vista, followed by what feels like a gut punch.

With a psychedelic color scheme, Richard Mosse’s Subterranean Fire, Pantanal (2020) uses multispectral imaging to reveal an underground fire in the Pantanal Wetlands, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in South America and one of the world’s largest tropical wetlands. “Underground fires are set, often illegally,” says NCMA curator Linda Dougherty, “to burn root systems and clear forests for agriculture. When looking at the bottom right corner of the image, you’ll notice a tiny white truck on the road with people nearby. They are trying to fight the underground blaze by pumping water, a seemingly impossible task given the scale of the fire.”

Farther north, in his exploration of the American southwest, Will Wilson utilizes drone photography to survey Abandoned Uranium Mines (AUMs) located on the Navajo Nation. Massive in scale and importance to America’s military during WWII, the AUMs are unavoidable reminders of the ugly and toxic histories layered onto Indigenous landscapes and forced upon tribes.

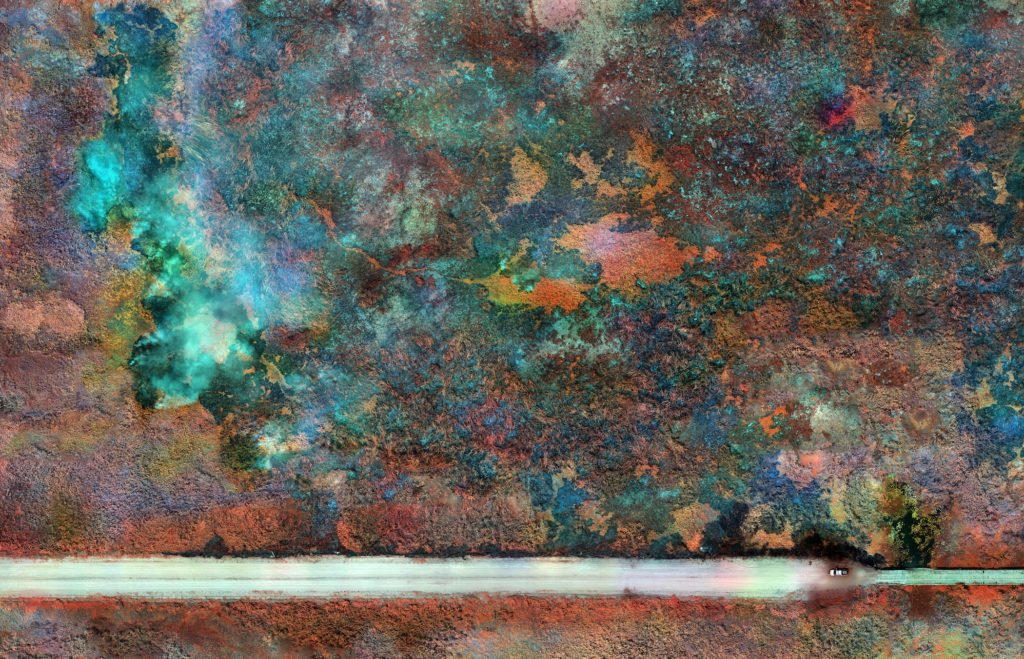

In Wilson’s Cameron Chapter Complex 1 (2020), the turquoise and clay hues of the southwestern landscape are disrupted by what appear to be scars on the earth’s surface. The curved white lines in the land are the visible remnants of attempts to conceal and contain the uranium mine that formerly operated there.

Wilson’s Connecting the Dots project seeks to raise awareness of the Navajo Nation’s efforts to receive remediation for the uranium extraction that has poisoned the land and threatened vital nearby water sources. Though different in execution than Mosse’s image, both photographs bring to light the kind of man-made catastrophes that are often, for one reason or another, hidden away from public view.

While there may be plenty of doom and gloom to be found, these exhibitions also offer us a vision of hope, and a chance at a different future–if we have the willpower to change course. Maybe the stories these images tell can help spark a shift toward the systemic change our environment desperately demands. If so, then the more eyes we can get on these images, the better.

In Raleigh Fault Lines is on view in the NCMA’s East Building through July 17. Will Wilson: Connecting the Dots is on view in Winston-Salem at SECCA’s Main Gallery through December 11. Admission to both exhibitions is free.

Black and: A Conversation about the Arts and Black@Intersection

The NCMA’s Moses T. Alexander Greene sits down with SECCA’s guest curator Duane Cyrus to talk about the diversity of Blackness, diversity in the arts, and how museums should foster both to create a sense of belonging and joy for all.