The vernacular photograph is a complex object that lives many lives before it comes to an art museum. I, like many people, use photography as a means of remembering, but in the case of vernacular photography, not all subjects in photographs are remembered over time. Once-cherished images of loved ones shed their context as family photos, mementos, and funny stories when they leave boxes in family attics and sell on eBay, Esty, or even Facebook. After they arrive at institutions like the Ackland Art Museum, they are preserved, housed, and remembered in a new context.

In my quest to learn more about the lives of vernacular photographs, I thought about their journeys from family or personal images to works of art hanging in museums for the public to see. I began by working backward, investigating photos at the Ackland that struck me.

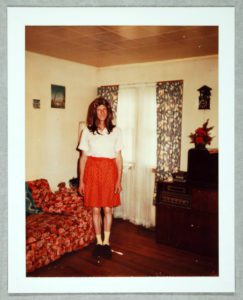

Consider, for example, this image of a man wearing a skirt. He is clearly posing, but we might speculate that this was a private image. The man stands in a domestic space, perhaps his own living room, where his skirt nearly matches the floral couch. In putting on a wig and skirt, he performs in a way that does not conform with heteronormative attitudes.

When I ventured into the storage room of the Ackland to study the image (which provided a good mock of viewing the photo in an attic), I was astonished by how small vernacular photos can be. The print fit in the palm of my hand, and the size told me it was meant to be held closely to see the details, suggesting a private and intimate viewing experience.

To further understand these objects, I contacted collector and UNC alumnus Robert E. Jackson, whose collection Man in a Blouse and Skirt once belonged to. With access to a market of millions of vernacular photographs, Jackson sometimes collects an image a day. Singling out a photo changes its fate. It goes from a family memento to a work of art. Jackson’s taste, choices, and collecting decisions brought Man in a Blouse and Skirt to the Ackland, where its private status and context changed.

My journey then took me to the North Carolina Museum of Art, where the collection boasts the work of photographers such as Diane Arbus and Nan Goldin—who both used the vernacular style but whose names carry more weight in art history than “unknown artists” of vernacular photographs.

Compare Goldin’s work titled Vivienne in the green dress, NYC to the image of the man wearing a skirt. Vivienne Dick, an experimental filmmaker, wears a vintage dress. Her hands are by her side in a pose nearly identical to that of the unidentified man. The subjects in both photos look directly at the camera, performing and posing in domestic spaces that complement their clothing.

Goldin often traversed the thin boundary between performance and privacy. She published Vivienne in a green dress, NYC in her first book, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Goldin started her book, “The Ballad of sexual dependency is the diary I let people read. My written diaries are private.” In this way Goldin affirmed the intimate quality of this visual work, as if peering into both her and her subjects’ lives in personal ways. Her work often also dealt with “the limitations of gender distinction.”

Following the life of vernacular photographs complicates what we make of the objects. By fate or luck, images that once documented a private moment become preserved in a museum. They are often filled with mysteries and unknowns, but they are art. By looking at vernacular photographs in conjunction with, rather than as separate from, other works of art and fine photography, we can learn from stories that were silenced, untold, or overlooked in documenting the banal, absurd, and forgotten.

Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design

Academy Award–winner in Costume Design, Ruth E. Carter has helped bring characters to life in acclaimed Hollywood blockbusters. The NCMA celebrates the magic of her imagination.

Innovative AIM Program Reaches Thousands

Thinking outside the lines, NCMA outreach programmers connect local artists in rural communities with local students excited to discover the artist within.

Love in the Galleries

This Valentine’s Day we invite you to follow Cupid’s arrow through West Building to discover some amorous works in the NCMA’s collection.