Provenance Research

Provenance research is the study of an object’s ownership history, from the time of its creation to the present day. Provenance is an essential tool to the understanding of a work of art and helps to ensure that museums collect in an ethical and legal way. Knowing the first owner or the original location of a work of art can help clarify the artist’s intention or deepen our interpretation of the work’s meaning or influence. An essential facet of art historical research, provenance provides insight into broader historical narratives, such as the biography of former owners, histories of the art market, and collectors’ tastes, which help us understand how collections are shaped and evolve over time.

It is rare to have complete provenance for an object, especially for those that are centuries old. Missing information might be due to lost, destroyed, or as-yet-undiscovered documentation or may be the result of the transfer of an object occurring without written records of exchange we would typically produce today. In exceptional circumstances research into the ownership history of an object can reveal changes in ownership caused by theft, plunder, or coercion.

As a fundamental part of its mission, the North Carolina Museum of Art is committed to a rigorous program of provenance research of the works in its collection and to the responsible resolution of any inquiries that may arise as a result of that research.

This page gives information about NCMA provenance standards, brief descriptions of provenance research and issues specific to different museum collections, resources for provenance work, and contact information.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Virgin and Child in a Landscape (detail), circa 1518, oil on panel, 16 1/2 × 10 1/4 in., Philipp von Gomperz Collection, Vienna, Austria (looted by the Nazis, 1940; restituted, 2000). Acquired by the North Carolina Museum of Art as the partial gift of Cornelia and Marianne Hainisch in tribute to their great-uncle Philipp von Gomperz, and as a partial purchase with funds from the State of North Carolina, Mrs. George Khuner, Howard Young, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, D. H. Cavat (in memory of W. R. Valentiner), Ernest V. Horvath, and Arthur Leroy and Lila Fisher Caldwell, by exchange, and Thomas S. Kenan III

Illegally confiscated by the Gestapo, 1940, ownership transferred from NCMA to Marianne and Cornelia Hainisch, heirs of Philipp von Gomperz, Vienna, 2000, re-acquired by NCMA in 2000.

Reading Provenance at the NCMA

What is the goal of provenance? Provenance should, ideally, provide a direct line of ownership starting with a work of art’s production by an artist (or discovery in the field in the case of antiquities) and ending with the date and manner in which said work entered the NCMA’s collection. In most cases a complete provenance is not possible to achieve, and research continues to be ongoing for most objects. Our provenances include the fullest and most accurate information known at the time of writing.

The provenance for a work of art in the North Carolina Museum of Art’s collection is listed in chronological order, beginning with the commission of the work, if applicable, followed by the place of creation from smallest to largest (village, city, state/region, country), followed by the date of creation.

For antiquities, provenience (if known from excavations and/or documentation or postulated based on stylistic studies) begins the provenance. Provenience is defined in this case as the location of the artifact at the time of discovery, which may or may not be a secure archaeological context. The names of artists are rarely applied to antiquities, so the point of origin is not the artist but the recorded (or postulated) findspot. If the artifact was excavated under controlled circumstances, the excavation details are included as well, as this becomes part of the provenance.

A note on punctuation: The names of dealers, auction houses, and agents are enclosed in brackets to distinguish them from private owners. Relationships between owners and methods of transactions are indicated by punctuation. A semicolon is used to indicate that the work passed directly between two owners, and a period is used to separate two owners if a direct transfer did not occur or is not known to have occurred. Footnotes are used to document or clarify information and are identified by brackets.

Sample Provenances

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Ivan Ivanovich Shuvalov (1727–1797), circa 1795–1800, oil on canvas, 33 × 24 in., Purchased with funds from the State of North Carolina

Created St. Petersburg, Russia, circa 1795–1800; the sitter or his family, St. Petersburg [1]; to his niece, Countess Varvara Nikolaevna Golovin (1766–1821), St. Petersburg; to her daughter, Elisabeth, Countess Leon Potocka (1801–1867); to her daughter, Leonie Wanda, Countess Casimir Lanckoronska (1821–1893), Vienna; to her son Count Karol Lanckoronski (1848–1933), Vienna; to his children Count Antoni (1893–1965), Countess Karolina (1898–2002), and Adelajda (1903–1980) Lanckoronski, Vienna; illegally confiscated by the Gestapo, Vienna, 1939 or November 1942 [2]; taken to Bad Ausee for Adolf Hitler [3]; recovered by the Allies and taken to Munich Central Collecting Point [4]; restituted to Countess Karolina Lanckoronska (1898–2002), Vienna, July 1946; [Frederick Mont and Newhouse Galleries, New York, by 1951]; sold to NCMA, 1952.

[1] The painting may have been painted posthumously.

[2] Jerzy Miziolek’s 1995 article, “The Lanckoronski Collection in Poland,” notes on p. 31: “… on 1st September [1939] the war broke out and the Collection as well as the palace were confiscated by the Nazis … It was the director of the Dresden Gallery, Dr. Hans Posse, who personally organized the confiscation … It is also known that in November 1942 Hans Posse again sent one of his collaborators to Vienna in order to inspect all the art objects in the collection remaining in the Lanckoronski palace.”

[3] Ausee nr. 568

[4] MNr. 645. The painting was received on June 24, 1945, and shipped out on July 30, 1946.

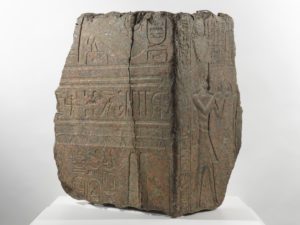

Egyptian from Sebennytos, Royal Offering Scene from a Temple, 285–246 BCE, granite, H. 29 in., Gift of the James G. Hanes Memorial Fund

Provenience (documented 1908 [1] and 1930 [2]), Sebennytos (Samannud), Egypt. Dikran Garabed Kelekian (1868–1951), New York, 1944–45. Avery Brundage (1887–1975), New York, before 1972 [3]. [Alan Brandt Gallery, Inc., New York, 1972]; sold to NCMA, 1972 [4].

[1] Ahmed bey Kamal, “Sebennytos et son temple,” in Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 7 (1906), 87–94 (see also 92, no. III).

[2] Edouard Naville, Détails relevés dans les ruines de quelques temples égyptiens (Paris, 1930), plate 16, A 3–4 (see also appendix on Samanood).

[3] In a letter dated November 6, 1972, Alan Brandt indicates that the relief was previously in the collection of Avery Brundage, Olympic athlete and fifth president of the Olympic Committee (NCMA curatorial file). Additional documentation has yet to substantiate this claim, and it is currently unknown whether Brandt acquired the relief directly from the Brundage collection.

[4] The relief was purchased with funds donated to the NCMA from the James G. Hanes Memorial Fund by Gordon Hanes. (Letter dated December 7, 1972, to the NCMA from the Trustees of the Fund and letter dated December 7, 1972, from Moussa Domit to Gordon Hanes, NCMA curatorial file).

Mexican, Chiapas state, Maya, Ball Court Marker, circa 550–850, limestone, H. 23 1/8 × W. 24 × D. 2 in., Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Gordon Hanes

Possible provenience, Chiapas, Mexico [1]. Gordon Hanes (1916–1995) and Helen Copenhaver “Copey” Hanes (1917–2013), Winston-Salem, 1980–82; gift to NCMA, 1982.

[1] Karl Herbert Mayer, Maya Monuments of Unknown Provenance in the United States (Ramona, 1980), 69.

African Art

Though the first works of African origin to enter the collection came to the Museum in the late 1960s and 1970s, the bulk of the Museum’s African collection dates back to the colonial period. This period ranges from approximately the 1880s until the first African countries began to gain independence, beginning in 1957 with Ghana and stretching into the 1960s and 1970s. This colonialist period flushed large volumes of artifacts onto the shelves and into the storerooms of private and public collections in Europe and then the United States. The NCMA recognizes the inherent ties between colonial administration and the creation of African art collections globally, including public museum collections in North America.

During the colonial period, negative stereotypes and perceptions of African peoples were cultivated through images, writing, and racialized theories of evolution. These stereotypes, meant to encourage support for the colonial project and its systematic exploitation of the continent’s resources, people, and environment, also resulted in very little information about the artists, places, and intangible heritage of African art being recorded at the time of collection. Missing information may also be due to lost or destroyed documentation or the transfer of objects without a written record of the exchange. In more serious cases, which may be revealed through provenance research, changes in ownership may be due to theft, looting, or plunder.

The NCMA is committed to researching its existing African collections and to the thorough investigation of prior ownership of any incoming objects of African origin. Should internal or external provenance research reveal a history of unethical collecting practices for any existing objects in the collection—which can include plunder during times of conflict or by unequal power relations at key moments in African colonial history, unethical collecting of culturally or spiritually sensitive materials, or theft from African museums—the Museum remains committed to working with stakeholder communities to make restitutions, returns, or reparations as agreed.

Provenance research ensures that the NCMA collects in an ethical and legal way, that the Museum actively acknowledges histories of exploitation and the inadvertent benefits to the art world, and that it maintains its collections within a spirit of collaboration, respect, and ethics.

Ancient Art / Antiquities

The widespread looting of objects from archaeological sites, through colonial appropriation, armed conflicts, terrorism, or organized crime, has produced a global market of undocumented antiquities of uncertain ownership.

With regard to antiquities, provenance includes not only ownership history but also the artifact’s archaeological findspot (specifically called provenience; see the Reading Provenance at the NCMA section for an expanded definition of the term). Antiquities bereft of archaeological context have lost much of their cultural meaning, function, and probable dating. The NCMA adheres to guidelines recommended by the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD).

The NCMA recognizes the role of antiquities as cultural emissaries for the history, ideas, and personalities that shaped the modern world. We feel that it is possible to collect responsibly, respecting the intent of laws, regulations, standards, guidelines, and executive orders on cultural patrimony, including but not limited to those of the American Alliance of Museums and UNESCO (Convention on Cultural Patrimony, 1970). We deplore the looting of archaeological sites and are determined to seek verifiable provenance for any object under consideration for acquisition. We submit all objects for review by appropriate registries, such as the Art Loss Register. While it may not be possible to trace every object to its origin, we will exercise due diligence with dealers, collectors, or any other source. After extensive ownership research, antiquities proposed in good judgment for acquisition without a complete provenance must be shown to meet the criteria for the acquisition of antiquities as recommended by the AAMD. Once accessioned, these objects must also be posted publicly on the AAMD Object Registry.

Approved by the NCMA Board of Trustees, June 5, 2013

European Art

Provenance research in European art has become more important in recent decades as we have learned the full story of the vast and systematic theft, confiscation, destruction, and forced sale of cultural property committed by the Nazi regime between about 1933 and 1945, something that is particularly applicable to European paintings and Judaic objects.

Though efforts were made after World War II to return stolen property to its rightful owners, thousands of paintings, sculptures, and other works of art remain unaccounted for.

Regarding Nazi-era provenance, the NCMA adheres to guidelines and procedures recommended by the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) and the American Alliance of Museums (AAM).

- Art Museums and the Identification and Restitution of Works Stolen by the Nazis

- Recommended Procedures for Providing Information to the Public about Objects Transferred in Europe during the Nazi Era

NCMA curators are working to identify all works in the People’s Collection that either changed hands in continental Europe between 1933 and 1945 or have gaps in their provenance during that period. These works are then posted on the Nazi-Era Provenance Internet Portal (NEPIP) administered by the AAM, a searchable database of art in United States museum collections with unresolved provenance during 1933–45. The NCMA has no reason to believe that any of its posted works of art were involved during the Nazi looting of European private and public collections. Works of art often pass from one owner to the next in ways that are legal if difficult to trace. Nevertheless, research is ongoing, and new information on provenance will be updated on this website, with the NEPIP, and in future NCMA publications.

New Acquisitions

As required by the NCMA’s collection management policies, the provenance of all works of art proposed for acquisition must be thoroughly investigated by the curators and a satisfactory report made to the Collections Committee of the Board of Trustees. If, after diligent research, the provenance of the work remains incomplete, the curators and director must determine with all due diligence that the incompleteness of provenance is not serious before an acquisition can proceed.

Selected Resources

- Yale University Art Gallery Provenance Research

- The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics

- Provenance #2, The Benin Collections at the National Museum of World Cultures

- Curator’s Choice: Provenance Research and Repatriation to African Communities

- Provenance Research at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin

- Africa Museum: Provenance of the Collections

Illicit Trafficking of Tangible Cultural Heritage

General Provenance Information

- IFAR Provenance_Guide

- Provenance Index Databases (Getty Research Institute)

- Frick Center for the History of Collecting

WWII

- Records of the National Archives and Records Administration Relating to Nazi-Era Cultural Property (National Archives)

- Art Provenance and Claims Records and Research (National Archives)

- Declassified Allied Records (free account required)

- Database of Art Objects at the Jeu de Paume

- Database of the Munich Central Collecting Point

- German Lost Art Database

- Site Rose-Valland, Depository of Stolen Goods

- Hermann Göring’s Art Collection

- ALIU “Biographical Index of Individuals Involved in Art Looting” (“Red-Flag” List)

All questions or information relating to the provenance of works of art in the NCMA collection should be directed to Michele Frederick, associate curator of European art and provenance research, via email or by phone, (919) 664-6766.