If you know anything about art, you know at least something about Picasso. If you know a bit more, you know about how Picasso and the cubists, expressionists, fauves, and surrealists copied African art, thinking they had found “pure” art and returned to the utmost source of creating. The modernists’ works were hailed by art history as expression, as aesthetic, as construction. Picasso was supposedly returning to the African “primitive” ideal, a state in which issues of aesthetic appearance and the expressive act of creation were prioritized over all else. But African art prioritizes neither of these things—because it’s not art. At least, not by Western definitions.

Every aspect of the African art-viewing experience has been colonialized, from how survey museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art and British Museum acquired their art (spoiler alert: through economic exploitation, “rescuing” it from disappearance, or stealing it), to how they categorized and displayed it, to how this art was viewed. Early exhibitions of African art grossly generalized African culture. Villages and cities, ethnic groups and cultural groups were oversimplified as “tribes,” stripping away their cultural specificities and interconnectivities. No distinction was made between cultural groups as objects were organized by type rather than by culture. Objects were chosen for their aesthetics and geometry; they were robbed of their dynamic nature, obscured in dim glass boxes, new coats of paint neglected, ritual anointings forgotten, crippled of their original uses. The rough surfaces enamored Western visitors, viewed as an indicator of the objects’ animalistic qualities.

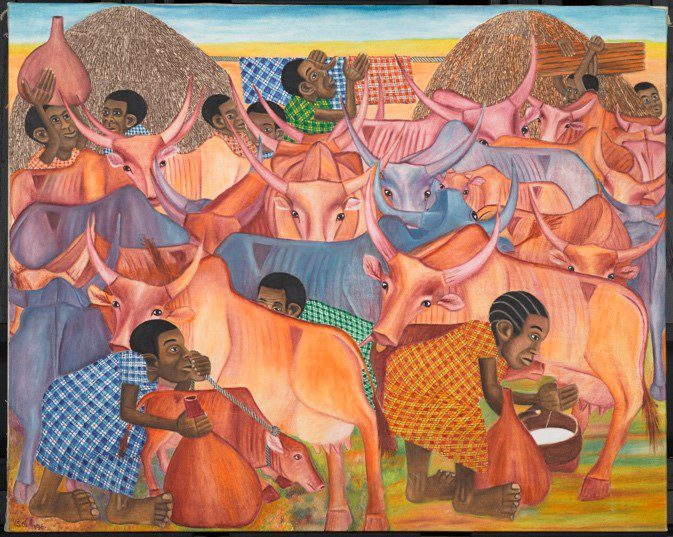

Yet African art surpasses the Western focus on surface. African art, in embodying something beyond the object, focuses not on the surface of an object but the space it takes up. The ere ibeji (twin) figures of Yorùbá culture, for instance, hold a certain weight to them, gravity that seems to vibrate from their cores. This emphasizes that the twin figures are not static objects and reminds the viewer of their profound significance—the essence of two twins, born of the same womb and connected by the same soul, that have been torn apart by death and now stand in eternal waiting. This embodiment of the universal, archetypal twin story is expressed on local terms, with bulging eyes and conical head that connect the twins to the cosmic realm, and a wide stance that indicates waiting. These motifs are not intended for aesthetic reasons but to embody these purposes and the very being of the waiting twin, thus exemplifying the Yorùbá saying “iwa l’ewa” (character is beauty).

Artists in 20th-century Africa did not typically see themselves as artists; rather, their profession was respected as craft, structuring ritual and perpetuating material culture. A mask carver in Sierra Leone is tasked not only with carving masks but lovingly repainting them after each dance so that the mask would fully evoke the being it was intended to. Thus, it was not the single fabrication but its upkeep and continued use that connected artisan and community with art object. The idea of creation as an originating act was arbitrary in 20th-century African art, since art objects in many places were viewed as mere vessels for something greater: in Chewa masquerade they are “things from the bush;” in Yorùbá culture, they contain ase, or spiritual authority; in Ghanaian popular art, they are physical stories. In focusing too much on the creation of the object itself, the viewer may miss “the point,” which is that there is something beyond the object itself, which holds visual power because it is a conduit for a greater, cosmological power.

Expressing the nuanced meanings and cultural references of African art presents curatorial challenges, forcing curators to think critically about the museum’s place in the writing of history. At the NCMA the African department has included videos to envision masquerades, interactive touch stations and questions on labels to encourage meaningful discussions, and provenance information into our research to expose painful histories. The Museum has worked to decolonize our sources of information by hosting talks with Black creators and focusing on Black collectors. Although this helps modify the museum space to fit the art it encompasses, it doesn’t erase the inherent problems that arise from taking these objects out of their specific contexts and putting them into a predominately white space intended for viewing rather than experiencing.

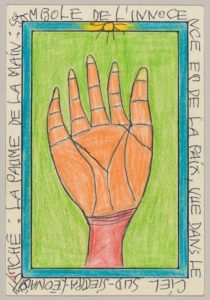

African art embodies, rather than reflects, the physical world. African art is imbued with the powers of ancestry (egúngún masquerade) and trickster or jokester personalities (Gongoli masquerade). African art reclaims power from colonial forces, subjecting it to local cosmologies and recompensing its evil wrongs (asafo company flags). African art defines new writing systems to articulate oral tradition, creates entire languages, and shares them universally (Frédéric Bruly Bouabré). African art is lived within, created for, and understood by the city (Kenyan jua kali). African art becomes the city (Esther Mahlangu). African art structures gender norms and social roles (Kuba cloth), prides its cultural identity (bògòlanfini and kente), and praises its wearer (Senegalese sañse). African art was not created for museums, and museums in turn were not created for it: it is dynamic, it is lived, it is in motion, in action and interaction, defining and subverting entire cosmologies, oppressive systems, and collective worldviews. It can’t fit into the global West’s glorified box that is the museum, that misappropriates it as a symbol of underdevelopment and primitivism, and it sure as heck can’t be described by people like Picasso who copy it just because it looks pretty.

“Art” in the Western context was defined originally as a physical reflection of the world, then an emotional aesthetic representation of the world, then finally as anything that you could put in a museum or call art, an idea pioneered by Marcel Duchamp and his ready-mades. So how can we categorize African art as “art” when it is neither intended to reflect the world physically, nor express emotion through aesthetics, nor be subjected to Western modes of display?

The answer: we can’t. Because it’s not art. It’s better.

This post is an abridged version of the original, appearing in the NCMA’s Intern Blog.

Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design

Academy Award–winner in Costume Design, Ruth E. Carter has helped bring characters to life in acclaimed Hollywood blockbusters. The NCMA celebrates the magic of her imagination.

Innovative AIM Program Reaches Thousands

Thinking outside the lines, NCMA outreach programmers connect local artists in rural communities with local students excited to discover the artist within.

Love in the Galleries

This Valentine’s Day we invite you to follow Cupid’s arrow through West Building to discover some amorous works in the NCMA’s collection.