From time immemorial, illnesses and threats to our health have always worried us. As we are surrounded by uncertainty caused by the pandemic that has gripped our world, it may be of comfort to know that we’re not the only ones who have experienced sweeping waves of contagion and great illness. The NCMA curators and GSK Curatorial Fellow have pulled together stories from the collection that show how works of art have been used for healing by people of diverse cultural backgrounds and religion throughout the centuries, or were created to remember those who have proffered medical care in times of need.

One of the NCMA’s most treasured early Italian paintings is a Florentine altarpiece dedicated to medical saints Cosmas and Damian. Cosmas and Damian were third century Arabian-born twin brothers who embraced Christianity and practiced medicine and surgery without a fee.

In the painting they are depicted in the central panel as well-to-do Florentines—note their fur-lined and/or trimmed cloaks (they were doctors, after all). Cosmas and Damian became popular saints in medieval Europe, particularly on the Italian peninsula and Spain, where their cults grew during times of plague.

The NCMA painting was created in Florence around 1370, some 20 years after the Black Death—a devastating epidemic of Bubonic Plague—struck Europe and Asia, hitting the Italian peninsula especially hard (sound familiar?).

Its creation is not tied to a specific outbreak of plague, however, but to the ordinary devotion to Cosmas and Damian by a group of lay Florentines. The tall and narrow design of the altarpiece indicates that it was commissioned by a confraternity (religious society) or guild (trade organization) for their altar in a church.

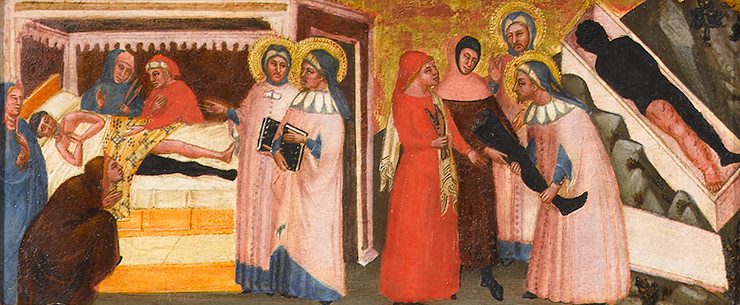

The two paintings in the smaller panels below the portraits illustrate legends associated with the two physician saints. On the left Cosmas and Damian cure a sick (white) man in Rome by replacing his diseased leg with that of a recently deceased but healthy (black) “Ethiopian”; on the right, they are martyred by Roman soldiers at the command of Emperor Diocletian.

The representation of the miraculous leg transplant (called the “Miracle of the Black Leg”) juxtaposed with a decapitation probably makes most viewers uncomfortable not only because of its graphic content, but also because of the stereotyped views of Africans it reveals. Why did the saints pilfer the body of a dead “Ethiopian”—meaning African—rather than a native Roman? And notice the shields of the Roman soldiers decorated with African heads, which were common motifs in medieval European heraldry. Notwithstanding these Eurocentric biases, the altarpiece is important because it stands at the beginning of a long visual tradition that portrays a perennial human concern: health and access to affordable (even free) medical treatment.

Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design

Academy Award–winner in Costume Design, Ruth E. Carter has helped bring characters to life in acclaimed Hollywood blockbusters. The NCMA celebrates the magic of her imagination.

Innovative AIM Program Reaches Thousands

Thinking outside the lines, NCMA outreach programmers connect local artists in rural communities with local students excited to discover the artist within.

Love in the Galleries

This Valentine’s Day we invite you to follow Cupid’s arrow through West Building to discover some amorous works in the NCMA’s collection.