Today curators and conservators sometimes ask a question rarely asked in the past: Is it appropriate to look at the ingredients of a power figure such as the NCMA’s Loma figure, and are we thereby accessing protected knowledge? Some may even ask, Is it safe? or Does the figure still contain a spiritual power or energy?

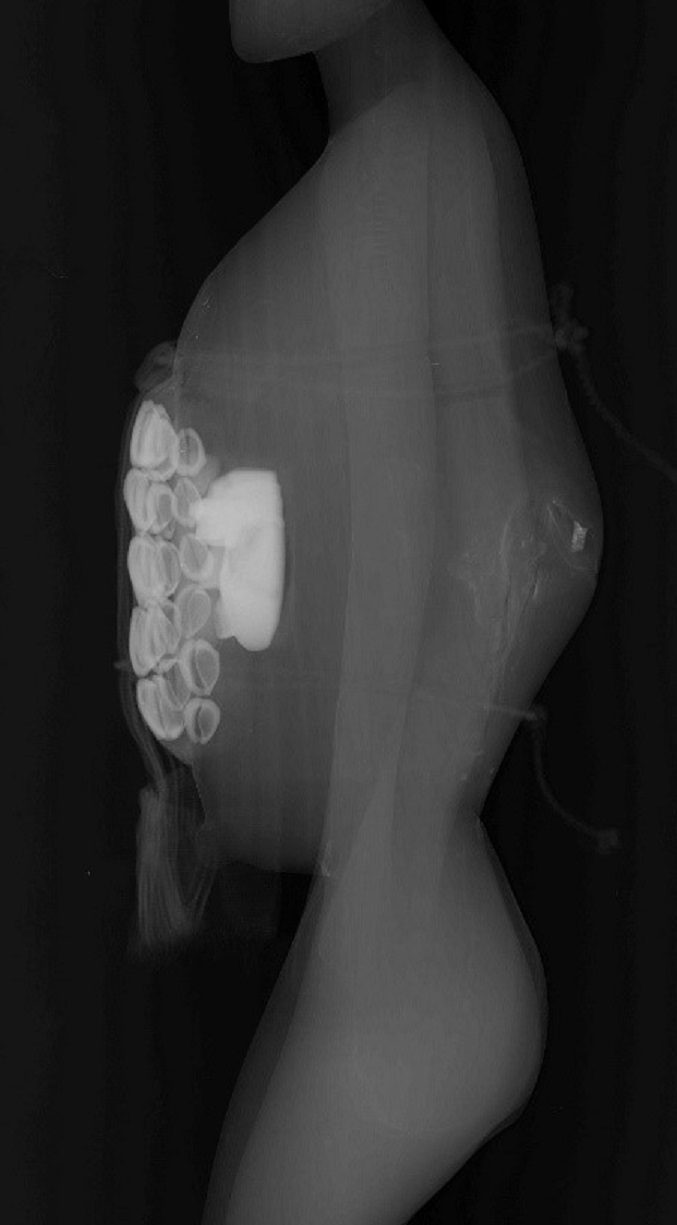

Uncovering hidden materials that were intentionally concealed inside a figure may seem invasive. These efficacious artworks were imbued with a power that was solidified through ritual applications of medicinal treatments, words spoken that activate the spirits and charge the piece, libations, and precise recipes and prescriptions packed within to treat ailments or effect a change. All of these things are private and specific, and often secret.

It has been argued that this power is temporary and must be reactivated time and again as the object is engaged with. Additionally, if the problem that the piece was created to treat is resolved, the piece is no longer useful, and its efficacy is reduced. Or if the object is not accomplishing its goal, the nonfunctioning work may be sold or destroyed and a new one created that may yield the desired results.

As Ghanaian curator and scholar Nii Quarcoopome wrote to me: “A power object needs to be ‘fed’ to keep it active. However, ‘inactive’ power is only latent and can be activated with the appropriate verbal incantations or treatment protocols. The objects that are intentionally disposed of are frequently stripped of their activating ingredients; those [figures] that are removed under questionable circumstances may simply be in a state of inertia!” In short, even when an object still contains its medicinal qualities, absent the knowledge of the incantations or proper procedures to “wake” the figure up (knowledge that is still very much secret), it remains in stasis.

How did these objects come to be in a museum, and did they leave the country with permission? Only by transparency and in-depth research can we hope to recover this history.

Evident here is another question surrounding the provenance and acquisition of such objects: How did these objects come to be in a museum, and did they leave the country with permission? Only by transparency and in-depth research can we hope to recover this history. It is the responsibility of museums housing objects of African origin to conduct such research. At this time we know who collected the Loma figure in Liberia and when; the process of tracing the rest of its history is underway.

While many of these objects have been deactivated and the power thought to once reside in them has diminished, they now have a new level of use and power, a different sort of inertia, as objects for scholarship and contemplation in a museum. As scholars, curators, and conservators look beneath the surface into what could be deemed secretive knowledge, we are not uncovering the precise meanings of the ingredients, only basic material identification. This identification helps the museum determine the best methods for preservation and conservation. When objects transition into museums, they have not lost their power; it has simply been converted into a different sort of power in their new lives.

And this next level of knowledge-power-inertia can increase exponentially if it is valued, shared, discussed, and debated both within museum communities and beyond.